It could be argued that successful investing is more about patience and time than anything else. The journey can at times be bumpy, with events triggering volatility and uncertainty. Last year was the perfect example of when market and geopolitical events combined to serve up a cocktail of uncertainty making investing for some extremely challenging. As we reach half-time in 2023, what has happened so far and how has that affected different investments? What are the prospects for the remainder of this year and beyond? Simon Durling from Santander Asset Management shares his thoughts in this week’s State of Play.

Key highlights from this week’s State of Play

- 2023 key events

- Asset class performance

- Second half outlook

2023 Key events

Investors, amateur or professional alike, all try to sense future market direction, regardless of when they are investing. Our natural instinct is to view history using the rear-view mirror, often believing this provides sufficient insights into predicting what might happen next. The last few years, including the global pandemic, have probably heightened this appetite for investors to understand the difference between uncertainty and probability. It could be argued that last year was a ‘one in one hundred years’, given all asset classes were falling at the same time for prolonged periods. Indeed, 2022 was the worst year for bond investors since records began.1 So, what were the key events in the first half of this year and why?

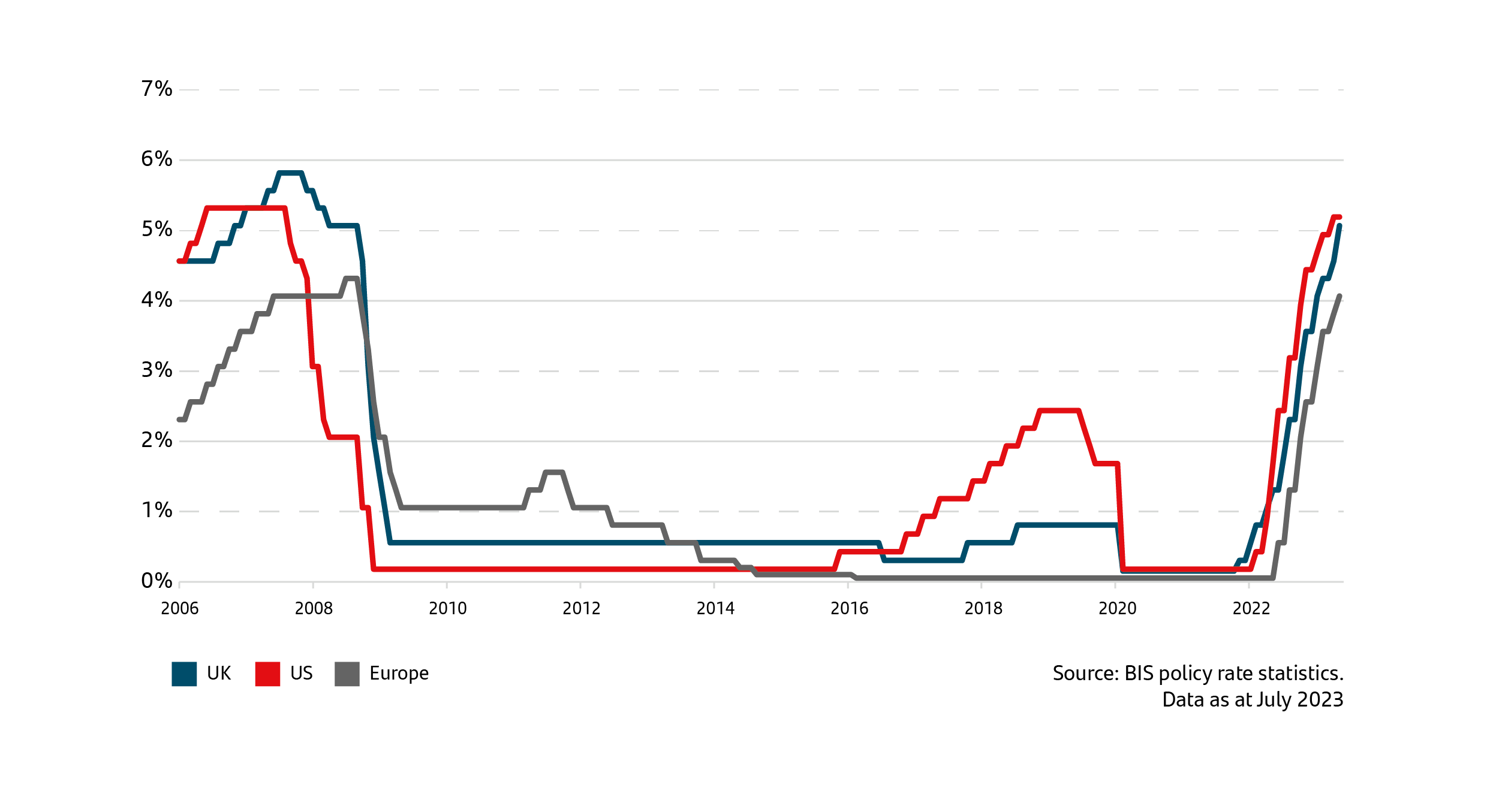

Central Banks continued to raise interest rates

Virtually all the central banks around the world, led by the Federal Reserve (the Fed) in the US, have continued raising rates to combat inflation. Many of the market participants minds have been obsessed with trying to second-guess how high these rate rises may go and, crucially, when would policymakers choose to pause. Certainly, in the first quarter of this year, against the expectation of falling inflation, some investors prematurely started to price in an early pause, even suggesting central bankers may even start to cut rates towards the end of 2023. The most recent narrative from the Fed, the Bank of England, and the European Central Bank (ECB) is that they expect to continue raising rates and keeping them higher for longer until the fight against inflation is finally won. All have warned against expecting them to pivot towards cutting rates anytime soon.

Interest rates

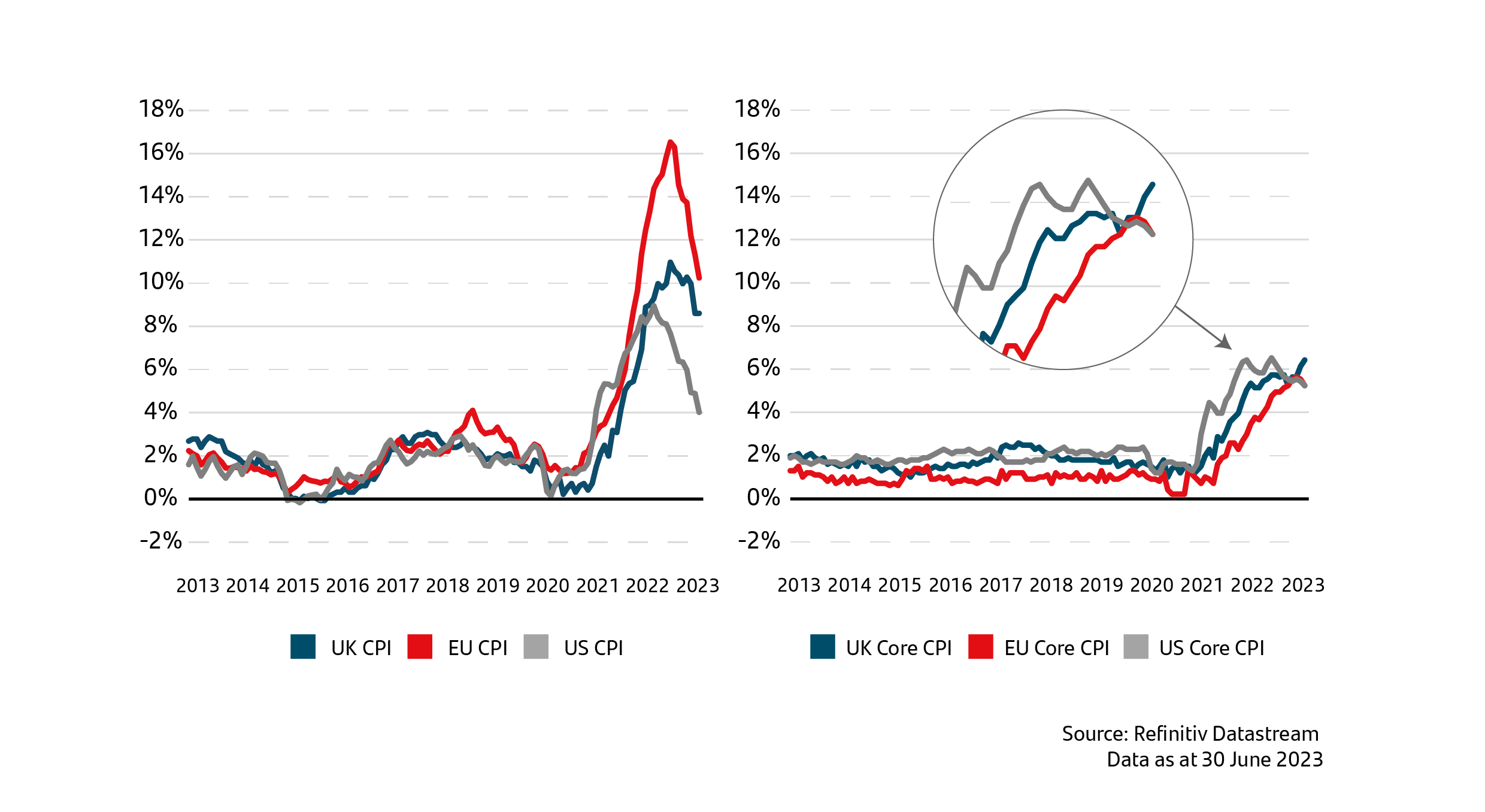

Core inflation remains stubbornly high

The return of inflation throughout 2022 has triggered the reversal of low interest rates and loose monetary policy. The challenge facing policymakers is how to bring down inflation without crashing the economy. The reason this may not be straightforward is in part because much of the cause of rising prices in the last couple of years has been more expensive raw materials, especially energy prices, and higher wage costs. The normal mechanism to control rising prices is to increase interest rates. Higher borrowing costs reduced disposable income and slowed consumption, so price rises started to reduce. However, while the initial spike in energy costs has dramatically reversed, leading to lower energy bills and petrol prices, core inflation remains high. This measure excludes both food and energy prices, which in the UK last month increased from 6.8% to 7.1%.2 The issue with higher wage settlements is what is known as the secondary effect, which I covered a couple of weeks ago. When people receive higher wages, they tend not to put money aside to cover the increase in their shopping basket or bills but instead start to spend what initially looks like disposable income, making it harder to reduce inflation.

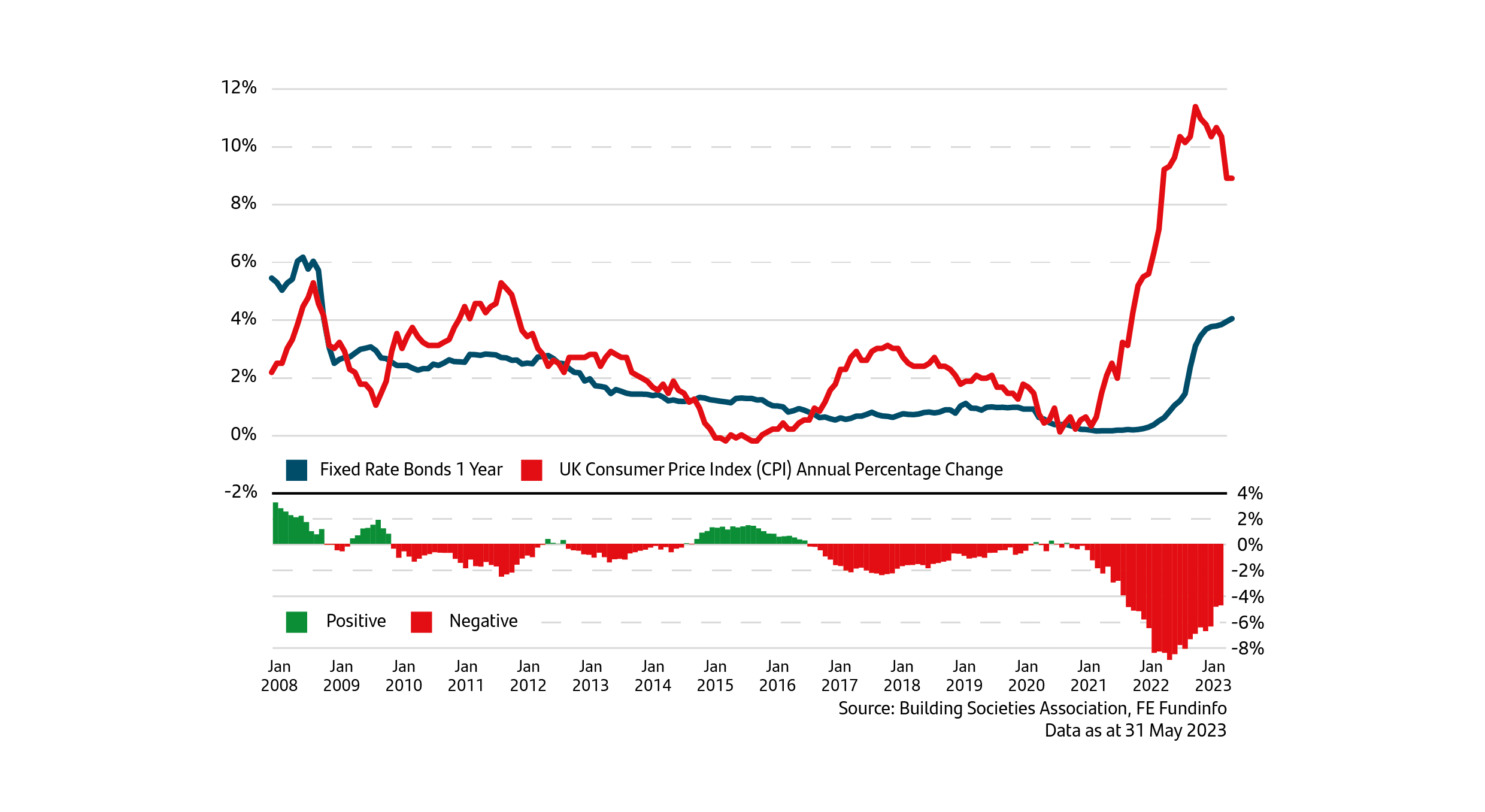

10 year annual Consumer Price Index

Banking crisis prompts concerns about a possible credit crunch 2.0

In early March, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) provided an update to the market that prompted a surge in customer withdrawals, which ultimately led to its demise, the largest bank collapse since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Credit Suisse, the 167-year-old Swiss bank, had to be rescued by its rival, UBS, swiftly followed by the collapse of First Republic in California. While SVB’s collapse was in the main caused by their concentrated business model, the rapid rise in interest rates prompted a domino effect leading to the crisis. The subsequent ramifications for the financial sector saw bank and financial company share prices take a hit and lending criteria start to tighten, making it harder and more expensive for both individuals and businesses to borrow money. The scars of the global financial crisis run deep, and although this happened 15 years ago and the regulations require most banks to maintain a minimum level of capital to protect against shocks such as these, it still stirs immense anxiety and the stock markets reacted accordingly.

The debt ceiling political football game happened again

As we approached the middle of May, the cyclical political duel in the US over whether to raise the debt ceiling raised its ugly head once again. This sent jitters through the market for a short time before finally President Joe Biden sat down with his political rivals to arrive at a suitable compromise. The agreement puts off the next debate on the ceiling until after next year’s Presidential Election.

Asset Class Performance

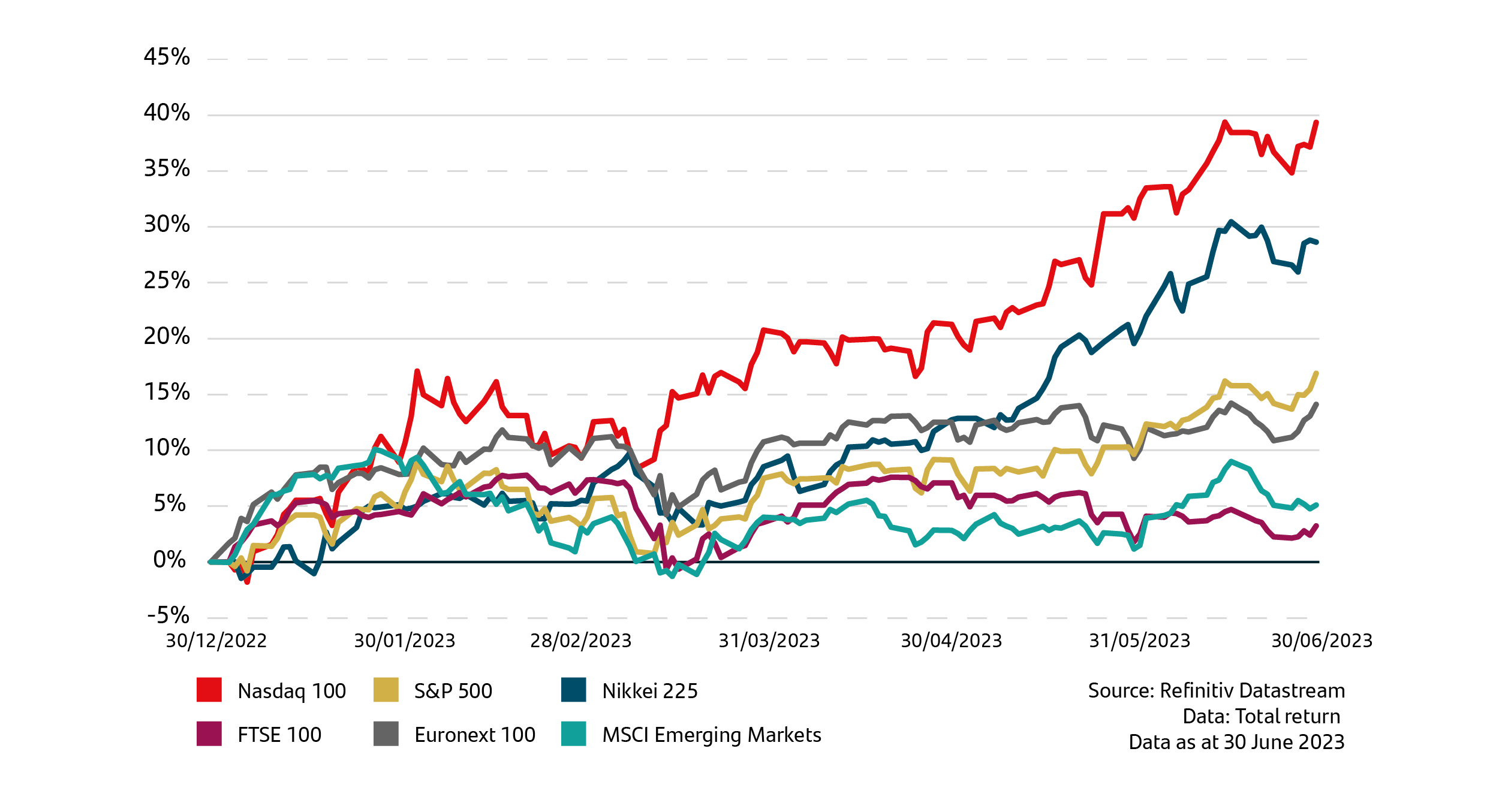

Shares

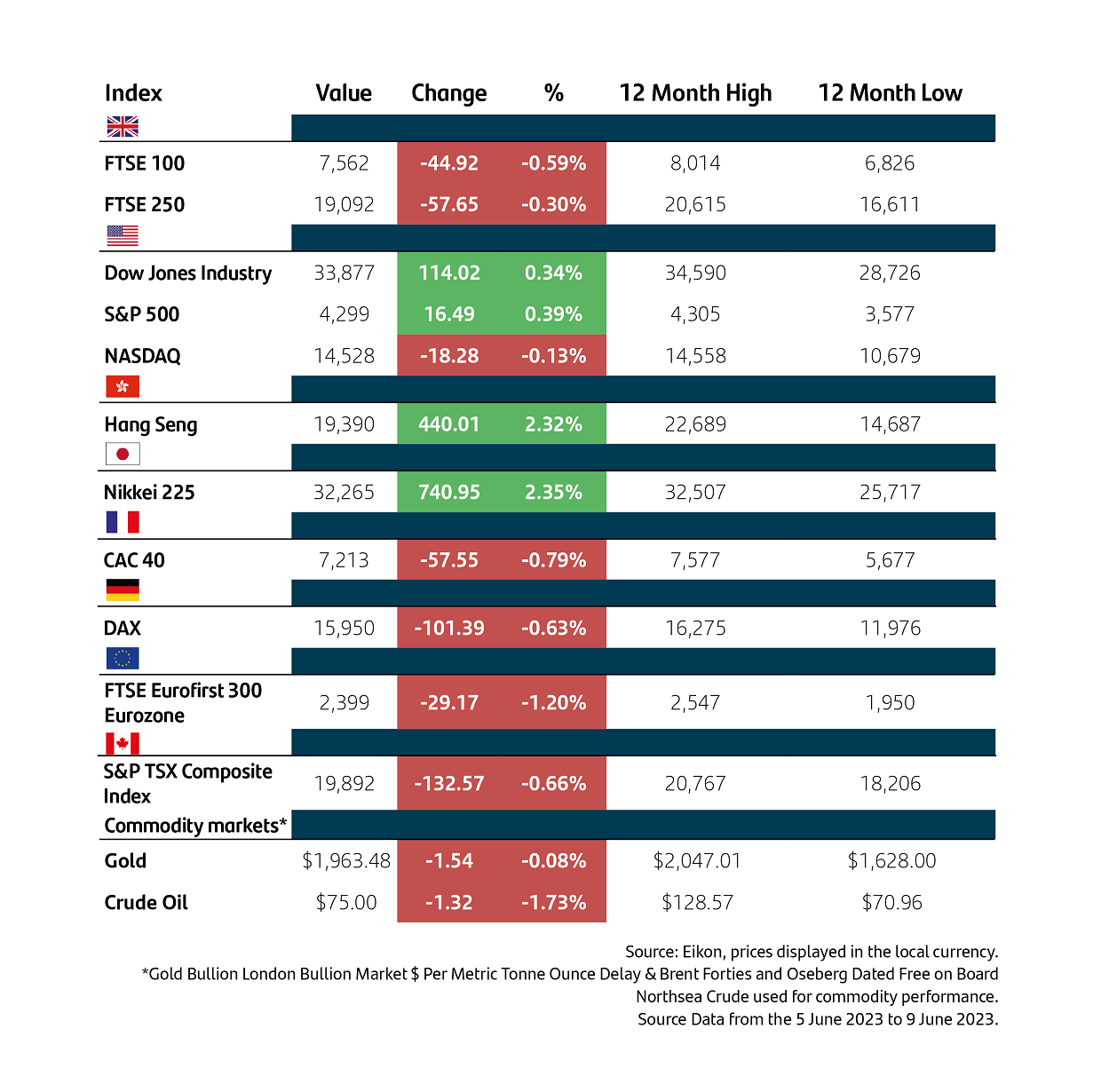

Depending on which stock market you focus on shares have been on, a bumpy journey in 2023, driven in part by the key events described earlier. However, when you reflect on how eventful it has been, it is easy to be swept away by the gloom and uncertainty and expect investors in shares to have lost money this year. However, this is not the case at all. Whilst there are big variations in regional performance, those invested in a diversified portfolio of purely shares will have performed much better than most people think. While the leading shares in the UK, the FTSE 100 has delivered just over 2% for the year and Emerging Markets are flat, all other markets have performed strongly, with the technology dominated NASDAQ up over 30%. The results do not reflect the journey.

6 month share index performance

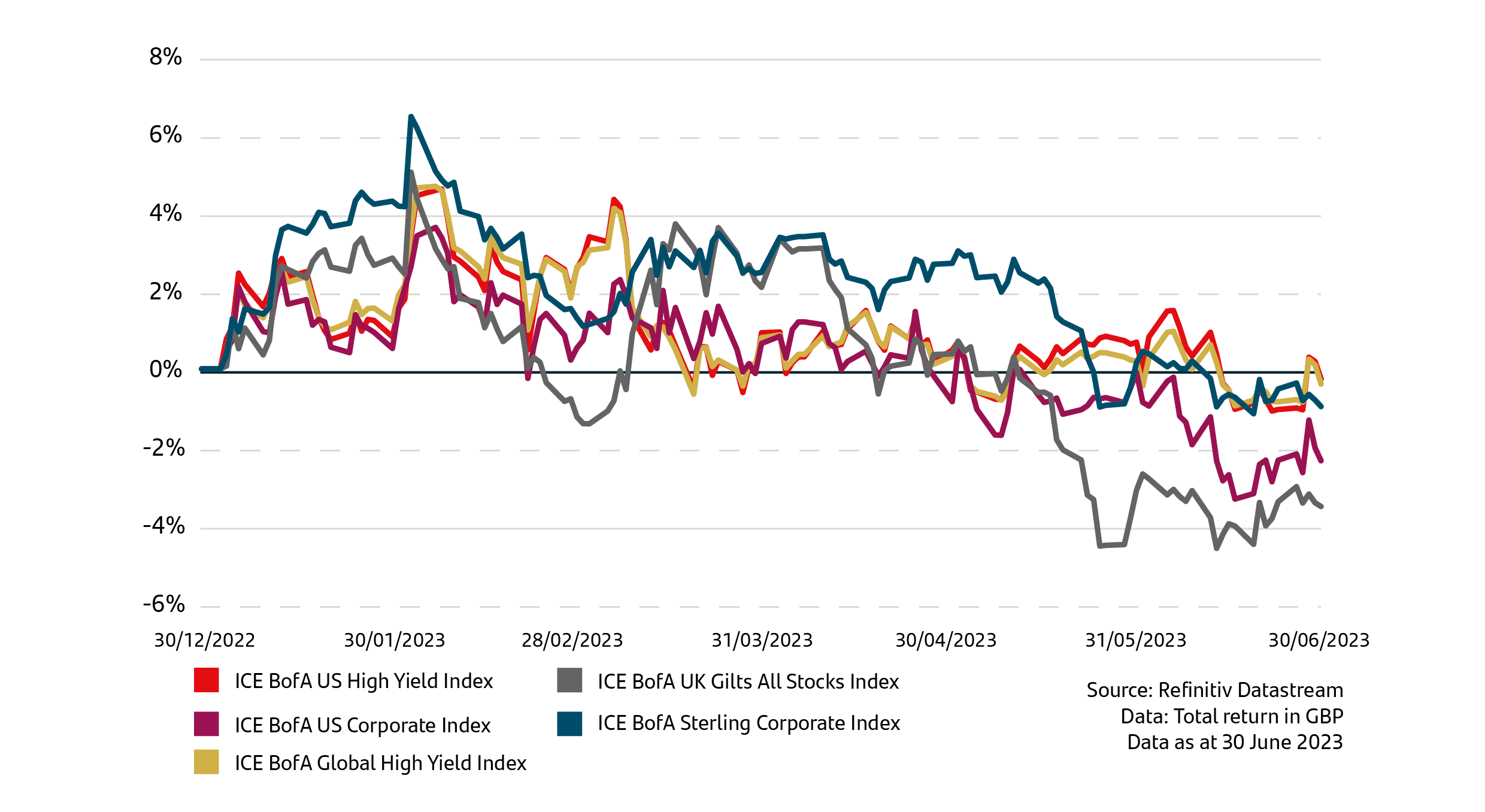

Bonds

Bonds

As we have explored in previous updates, last year was the worst investment performance for bond investors in history. With rising yields at the start of the year, expectations of a peak in rates helped bonds make a strong start. However, as inflation proved to be stubborn, falling slower than central banks and policymakers had hoped for, yields from March onwards began to rise back up, as bond investors priced in higher rates for longer. Bond values fell in response, with UK Gilts the biggest loser with a minus 3% performance year-to-date.

6 month bond index performance

Second half outlook

After such an eventful first half, it is tempting to think the rest of the year will be much quieter and less volatile. However, given how far and how fast central banks have raised interest rates to curb inflation, the current resilience shown by most global economies is bound to be impacted eventually. Depending on which country or region you focus on, there are certain nuances that become clearer when you explore the subtle differences in the challenges they face in their immediate future.

In the US, a tight labour market, robust consumer confidence and the ability of the US economy to keep creating new jobs, continues to defy forecasts and expectations. However, we are fast approaching the starting pistol to next year’s Presidential Elections in November 2024. The Federal Reserve Chairman has warned markets that the rate rises are not yet finished and that investors should not expect rate cuts anytime soon. Policymakers’ determination to bring inflation back under control regardless of the economic consequences, where they would prefer to go too far with rate rises than not go far enough, provides a significant headwind. Typically, when investors assess the rates on short-term government borrowing when compared to the longer-term rates, you would expect in normal market conditions for investors to be rewarded with higher rates over the long-term. However, markets are faced with what is described as an inverted yield curve, the complete opposite. 1 year government bonds are well above 5%, while 10-year rates are below 4%.3 Why is this significant? Well, most economists and market experts would predict a recession is imminent when the yield curve is inverted, like now.

In the EU, Germany has already fallen into a technical recession in the first half of this year as the European Central Bank (ECB) was late to the party in raising rates when compared to both the UK and US. The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) last week decided to be more aggressive with a higher rate rise than previously predicted on the back of disappointing core inflation data, as prices excluding energy and food went up, not down, in May. They now expect inflation to stay higher for longer and have warned market participants to brace themselves for further rises, and again, like their US counterparts, forecasting no cuts to rates any time soon.

Inflation remains the number one threat and the implications for economies if price rises are not tamed soon are stark. We have already seen in the UK that a combination of a tight labour market with over 1 million vacancies and higher wage settlements than their international peers is likely to slow inflation’s stubborn decline. The UK is a prime example of why interest rate rises are a blunt tool. As I explained a couple of weeks ago, when the MPC raises rates, it immediately raises borrowing costs for all. There are still just under 2 million mortgage borrowers who have a fixed rate ending between now and the end of next year. The rate they will have been paying and the packages available now and in the immediate future will be significantly higher, leading to a big jump in their monthly mortgage payments.

This lag effect of raising interest rates takes time to feed into lowering disposable incomes. Policymakers cannot be sure when the rate rises will be enough. Also, while the banking turmoil in March appears to have dissipated for now, the lasting impact on the lending criteria of banks and their desire to hoard more cash just in case a repeat event happens in the next few months means that for borrowers, whether this be businesses or individuals, costs are higher and the available credit is probably lower. Tighter lending conditions over time tends to act like a further interest rate rise, as anybody looking to renegotiate their mortgage deal right now will tell you.

In conclusion, some important observations about what has happened so far and what we can expect. Firstly, if you simply concentrate on the latest story or crisis, you would be forgiven for thinking investing is simply not worth it. In addition, many who are tempted by the much higher cash rates available on their savings might conclude that investing isn’t worth the risk. However, as we have seen, investment returns have been better than they perhaps feel. While we should celebrate higher savings rates after such a prolonged period of near zero interest, the gap between inflation and the best rates is wider now than before rates began to rise. The erosion gap, as I like to call it, remains the biggest threat to long-term wealth and the reasons for investing have not changed. Investors are normally rewarded for their time and patience, provided they have an appropriate, diversified portfolio aligned to their investment risk comfort, long-term objectives, and timeframes.

The erosion gap

The value of seeking guidance and advice

It is important to seek advice and guidance from a professional financial adviser who can help to explain how to build an appropriate financial plan to match your time horizons, financial ambitions, and risk comfort. If you already have a plan in place, or have already invested, it is important to allocate time to review this to ensure this remains on track and appropriate for your needs.

Performance

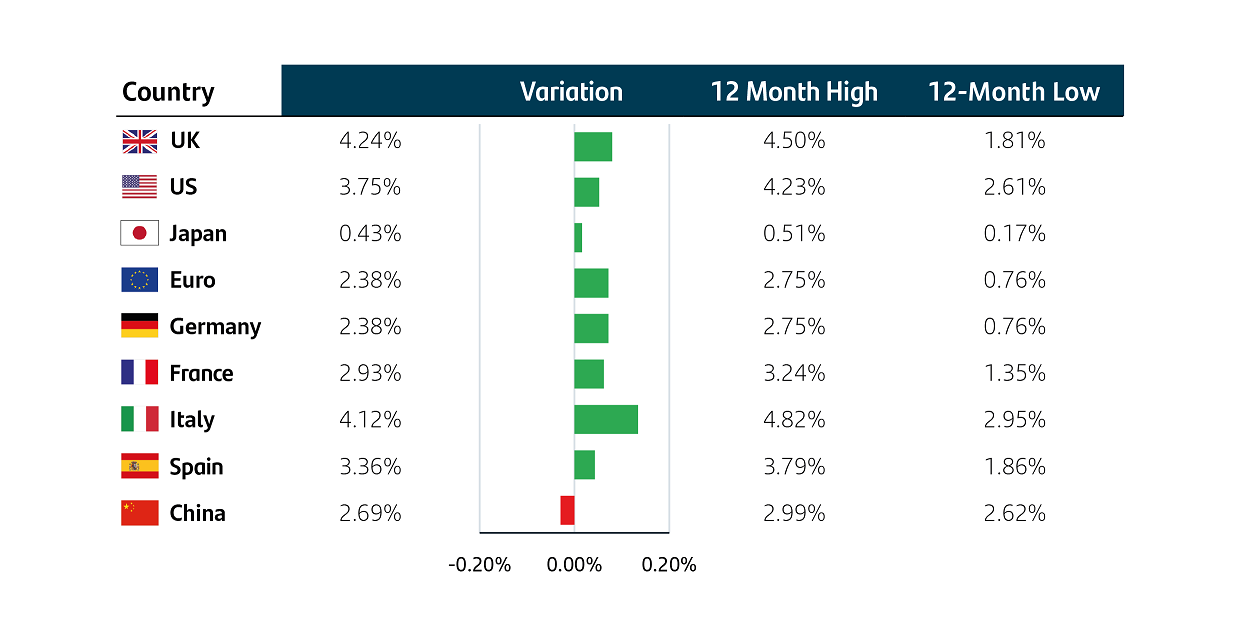

10-years bonds yields

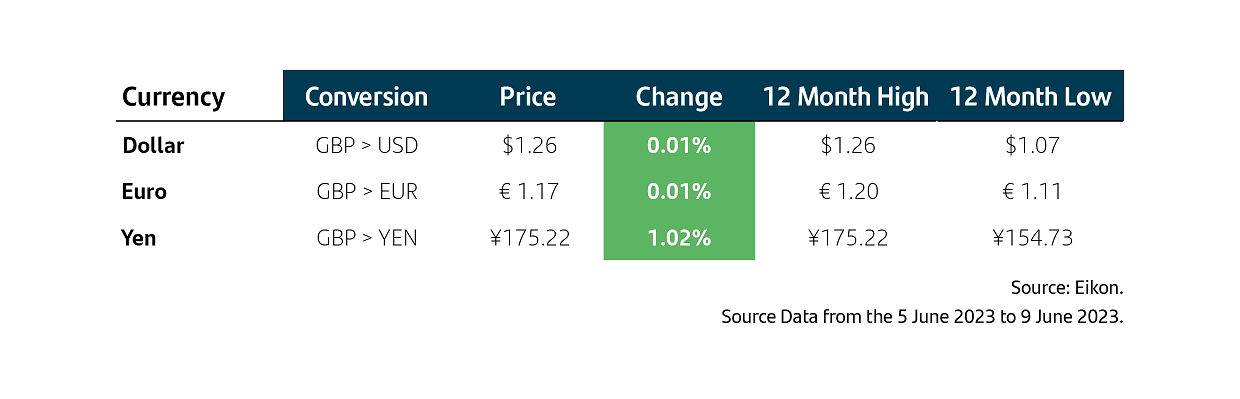

Currencies

Investing can feel complex and overwhelming, but our educational insights can help you cut through the noise. Learn more about the Principles of Investing here.

Note: Data as at 6 July 2023. 1CNBC, 7 January 2023. 2Office for National Statistics (ONS), 21 June 2023. 3Investing.com, 30 June 2023.

Important information

For retail distribution.

This document has been approved and issued by Santander Asset Management UK Limited (SAM UK). This document is for information purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments, or to provide investment advice or services. Opinions expressed within this document, if any, are current opinions as of the date stated and do not constitute investment or any other advice; the views are subject to change and do not necessarily reflect the views of Santander Asset Management as a whole or any part thereof. While we try and take every care over the information in this document, we cannot accept any responsibility for mistakes and missing information that may be presented.

The value of investments and any income is not guaranteed and can go down as well as up and may be affected by exchange rate fluctuations. This means that an investor may not get back the amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

All information is sourced, issued, and approved by Santander Asset Management UK Limited (Company Registration No. SC106669). Registered in Scotland at 287 St Vincent Street, Glasgow G2 5NB, United Kingdom. Authorised and regulated by the FCA. FCA registered number 122491. You can check this on the Financial Services Register by visiting the FCA’s website www.fca.org.uk/register.

Santander and the flame logo are registered trademarks.www.santanderassetmanagement.co.uk