As calm returns to investment markets after a stormy first quarter, you would be forgiven for thinking that investors will soon be able to see light at the end of the current infamous investment cycle. However, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) this week warned that central banks face tough choices ahead that have the potential to catch more unsuspecting banks in a credit crisis amid a much gloomier outlook for the world’s economy. Our Senior Investment Specialist, Simon Durling, shares his thoughts in this week’s State of Play after returning from the Easter Break.

Key highlights from this week’s State of Play

- Quick guide to the International Monetary Fund (IMF)

- Dark clouds predicted for the UK in the new IMF forecast

- IMF warning - credit crunch 2.0?

- Outlook

International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Conflict often brings about significant changes affecting our day-to-day lives, not least of which are the long-term financial consequences of war. It is possible to trace back through history the financial evolutions triggered by the need to fund conflicts and the ability of those in power to cushion the costs of war. The origins of the Bank of England are directly linked to England’s war with France. In the late 17th century, those in power copied an idea first tested in ancient Greece, then perfected in medieval Italy, and finally utilised by the Dutch to gain a telling global trading advantage: borrowing from ordinary citizens.1 The reason for this unusual introduction is to point out the link between historical conflicts and our modern financial world. One organisation whose origin can be traced to arguably the biggest war in history is the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

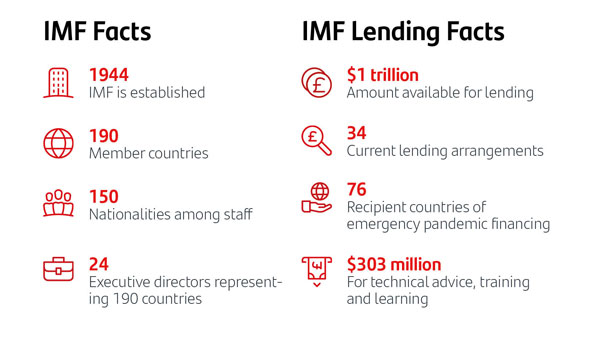

On 1 July 1944, just weeks after the invasion at Normandy began, 730 representatives sent from 44 countries around the world met at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. Their sole purpose was to discuss, debate, and decide on a system of economic rules and international collaboration to help countries recover from the devastation caused by the war and begin to plan a more prosperous financial future. The Bretton Woods Conference, as it became known, was pivotal in shaping a new financial order designed to provide financial stability and targeted support in pursuit of long-term global economic growth for all. When the meeting ended, the Articles of Agreement for two organisations were successfully concluded: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) – now known as the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2 & 3

These organisations had three crucial objectives: supporting the expansion of trade and economic growth, promoting international monetary cooperation and discouraging policies that may harm future prosperity. The two other significant agreements reached at the conference were to set up a stable system of exchange rates linked to the dollar and to provide financial support in the form of loans to help pay for the rebuilding of damaged European economies. When the IMF was formed, it began with 40 member countries, which have grown to 190 today, of which 150 are represented by those who work for the organisation. Importantly, the IMF is accountable to the member countries and collects quotas from each country dependent on its size and position in the world economy.3

Over the years, there have been famous interventions from both the IMF and the World Bank, supporting directly or advising from the side-lines.3 From a UK perspective, the most famous of these came in 1976, triggered initially by the oil crisis of the early 1970s, causing soaring inflation and the devaluation of the pound against the dollar, eventually forcing the UK government led by James Callaghan to agree to an IMF bailout of $3.9 billion, the largest ever agreed at the time.3

A new but gloomier IMF global economic forecast

This week, the IMF published its latest global economic forecast, consisting of 206 pages of detailed analysis and some important predictions and warnings closely watched by both policymakers and investment markets. It predicts lower global growth because of sustained higher inflation, the sharp rise in interest rates over the last 18 months and the failure of wages to keep pace with price rises, which will lead to an inevitable slowing of growth in the next couple of years. The opening paragraph in the foreword captures a precise summary of recent events:

“On the surface, the global economy appears poised for a gradual recovery from the powerful blows of the pandemic and of Russia’s unprovoked war on Ukraine. China is rebounding strongly following the reopening of its economy. Supply-chain disruptions are unwinding, while the dislocations to energy and food markets caused by the war are receding. Simultaneously, the massive and synchronous tightening of monetary policy (increasing of interest rates) by most central banks should start to bear fruit, with inflation moving back toward its targets.” 4

Among the many forecasts, the UK is predicted to be one of the worst performing advanced economies over the next two years, with the IMF expecting the UK economy to contract in 2023 and for the debt burden to exceed 100% of GDP. The analysis breaks down debt and deficit levels in the world economy, the IMF said the UK’s net debt pile would steadily rise from 91.9% to 101.2% of GDP by 2028. One of the reasons for the UK’s gloomy outlook is that they disagree with the forecasts provided by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the government’s independent economic forecaster. Vitor Gaspar, the IMF’s director for fiscal affairs, did however compliment Jeremy Hunt, the UK Chancellor, on his medium-term approach: “We are actually quite impressed by the way the budgetary procedure with an emphasis in the medium term is working in the UK. What you see is that there is an increase in public debt in a couple of years and then a stabilisation follows if the government’s and the OBR’s forecast proves correct.” 4

Credit crunch 2.0?

The report provides additional warnings to policymakers about the need to be flexible in their approach to further interest rate rises, with specific concerns about other banks or financial organisations being caught in the crosswinds. The IMF report states, “Policymakers should act swiftly to prevent any systemic event that may adversely affect market confidence in the resilience of the global financial system. Should policymakers need to adjust the stance of monetary policy to support financial stability, they should clearly communicate their continued resolve to bring inflation back to target as soon as possible once financial stress lessens.”

This warning relates to the recent banking crisis where Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in the US collapsed and Credit Suisse needed to be bailed-out by its rival UBS. The IMF explains that further rate rises may catch other institutions, who may become vulnerable if exposed to any doubts about their liquidity safety nets or a loss of confidence by their depositors. Whilst the fund didn’t anticipate any other crises, it did explain that if rates go too high for too long, a return of investor nerves may require central banks to act swiftly once more.4 These warnings were echoed by the Governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, who explained that due to technology, he fears banks may not have sufficient cash buffers to weather a depositor storm.

For now, confidence seems to have returned, and investors are reassured that the banking sector has weathered the first full blown test since the financial crisis. Last September, after the infamous mini budget, investor confidence evaporated as unfunded tax cuts prompted a spike in UK long-term debt yields, requiring the Bank of England to step in with emergency measures. This time round, central banks reacted quickly to avoid a wider systemic crisis following the run on SVB’S in the US and although banking and financial sector share prices took a battering, given the seriousness of what happened and the speed of SVB collapse, changes in capital requirements and other regulations and rules helped to protect the financial system we all rely on. I am certain that concerns about the wider financial system will weigh heavily on the central bank monetary policy committees in the weeks ahead as they assess whether to press the pause button.

Outlook

At the time of writing, markets remain nervous. The latest US inflation data showed a significant fall in overall inflation from 6% to 5%, mainly due to the base effects when measuring price rises against the same period last year as the Ukraine conflict escalated.5 Core inflation, however, remained unchanged at 5.6% alongside strong employment data, which in some ways leaves the jury out on whether these latest macro insights will sway the Fed to hold interest rates unchanged when they meet in early May.

In the UK, further signs of a slowdown may help the Bank of England (BoE) to also pause for thought. The UK economy remained flat in February as civil service and teachers’ strikes hit output in the services sector.6 This, coupled with a large financial sector in the UK exposed to any further credit nerves, is likely to sway the Monetary Policy Committee of the bank when they meet. In addition, lending appears to have tightened already in the wake of the banking crisis as banks restrict lending. The consequences of tighter lending conditions mean economic growth may be lower in the next few months, which is precisely what central banks aim to achieve with higher interest rates. Perhaps that penny may have finally dropped.

The BoE is looking at the prospect of reforming Britain’s bank deposit insurance guarantee scheme, which could result in greater client protection. Speaking in response to high-profile bank failures on both sides of the Atlantic, Andrew Bailey, the BoE governor, suggested that the UK might need to increase its limit for guaranteed deposits above the current £85,000 because the UK scheme was unlikely to work as intended for smaller banks. The UK Treasury will ultimately decide whether to raise the statutory £85,000 cap, which has been in place since 2017, acting on a proposal from the BoE.7

The value of seeking guidance and advice

It is important to seek advice and guidance from a professional financial adviser who can help to explain how to build an appropriate financial plan to match your time horizons, financial ambitions, and risk comfort. If you already have a plan in place, or have already invested, it is important to allocate time to review this to ensure this remains on track and appropriate for your needs.

Investing can feel complex and overwhelming, but our educational insights can help you cut through the noise. Learn more about the Principles of Investing here.

Note: 1Britannica, 24 March 2023. 2World Bank, 13 April 2023. 3IMF, 13 April 2023. 4IMF World Economic Outlook, 30 March 2023. 5Investing.com, 13 April 2023. 6Office for National Statistics (ONS), 13 April 2023. 7Financial Times, 13 April 2023

Important information

For retail distribution. This document has been approved and issued by Santander Asset Management UK Limited (SAM UK). This document is for information purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments, or to provide investment advice or services. Opinions expressed within this document, if any, are current opinions as of the date stated and do not constitute investment or any other advice; the views are subject to change and do not necessarily reflect the views of Santander Asset Management as a whole or any part thereof. While we try and take every care over the information in this document, we cannot accept any responsibility for mistakes and missing information that may be presented.

All information is sourced, issued and approved by Santander Asset Management UK Limited (Company Registration No. SC106669). Registered in Scotland at 287 St Vincent Street, Glasgow G2 5NB, United Kingdom. Authorised and regulated by the FCA. FCA registered number 122491. You can check this on the Financial Services Register by visiting the FCA’s website www.fca.org.uk/register